Otoplasty Chapter Co-Authored by Dr. Shah

For More Information on Otoplasty, see the Otoplasty Home Page.

Jeffrey B. Wise MD, Anil R. Shah MD, and Minas Constantinides MD

Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, New York University School of Medicine

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- Introduction

- Anatomy and Embryology of the Auricle

- Proportions and Aesthetic Considerations of the External Ear

- Preoperative Evaluation / Timing of Surgical Correction

- Techniques of Surgical Correction

- Complications of Otoplasty

- Summary

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

- Prominauris (prominent ears) occurs in approximately 5% of the population.

- Knowledge of anatomy, embryology, and normal aesthetic proportions is essential for accurate diagnosis and surgical treatment of auricular deformities.

- Conchal prominence and the absence of an antihelical fold represent the most common etiology behind prominence of the ears.

- Although there are hundreds of techniques to correct auricular prominence, the most common are suture techniques for conchal setback (technique of Furnas) and for creation of an antihelical fold (technique of Mustarde).

- Otoplasty refinement techniques exist for deformities such as large earlobes and excessive helical prominences.

- Complication rates from otoplasty range from 7-12%, and may be subdivided into early, late, and aesthetic/anatomic in etiology.

- Auricular hematoma occurs in 1% of otoplasties. Complaints of unilateral pain or tightness within the first 48 hours postoperatively requires prompt removal of dressings to examine the wound site for hematoma collection.

Deformities of the external ear, specifically prominent ear deformities, are relatively common. While posing negligible physiologic consequences, prominent ear deformities can be a source of profound psychological stress on the patient. Dieffenbach is credited with performing the first otoplasty in 1845 through resection of postauricular skin and conchomastoid fixation. Since that time, hundreds of techniques have been reported for correction of the prominent ear. Proper analysis, in combination with meticulous surgical technique, can optimize form, symmetry, and ultimately patient satisfaction.

ANATOMY AND EMBRYOLOGY OF THE AURICLE

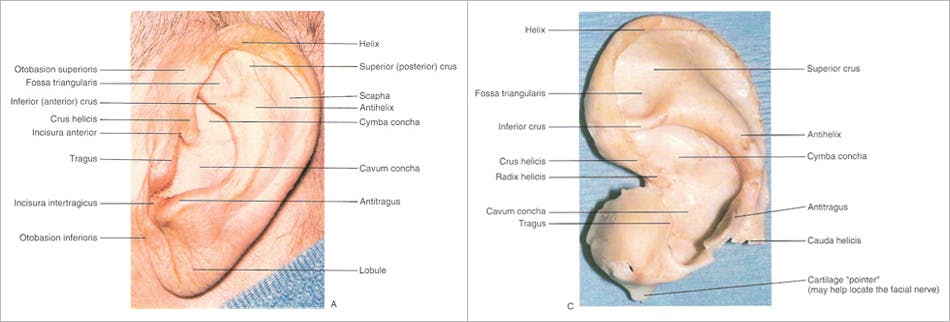

The external ear is a composite of cartilage and skin. Important topographic landmarks of the external ear include the circumferential structures of the helix, tragus, and lobule.

(Figure 1A)

These structures encase a multitude of well-described folds and involutions of the external ear, such as the conchal bowl, which is subdivided into the superior cymba concha and inferior cavum concha by the anterior helical crus. The antihelical fold courses superiorly and anteriorly, dividing into the superior crus and sharper inferior crus. The resulting depression that is formed between the antihelix and helix is known as the scaphoid fossa, and the depression that is formed between the superior and inferior crura of the antihelical fold is known as the triangular fossa.

Embryologically, auricular development is first seen in the 5-week embryo and stems from six mesenchymal proliferations, or hillocks, of the first (mandibular) and second (hyoid) branchial arches. These primative hillocks develop into mature auricular landmarks. The majority of these anatomic landmarks are derived from second arch structures (helix, scapha, antihelix, antitragus, lobule) and a less significant contribution is made by first arch components (tragus and helical crus).

The ear consists of 6 clinically insignificant intrinsic muscles (major and minor helices, tragus, antitragus, transverse, and oblique muscles) and 3 extrinsic muscles that contribute minor structural support to the ear (anterior auricularis, superior auricularis, and posterior auricularis muscles). The arterial blood supply to the external ear is derived from the superficial temporal, posterior auricular, and occipital arteries. Motor innervation to the external ear, which varies among individuals, is supplied by the facial nerve. Multiple nerves are responsible for sensation to the auricle, and include the lesser occipital, greater auricular, auiculotemporal, and Arnold’s (CN X) nerves.

REFERENCES

Wise JB: Otoplasty, in Ruckenstein MJ (ed): Comprehensive Review of Otolaryngology.Philadelphia, Saunders, 2004; p 273.

Janis JE, Rohrich RJ, Gutowski KA. Otoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 115:60e, 2005. UI: 15793433.

Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL: Surgical Anatomy of the Face, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, p 171-172.

PROPORTIONS AND AESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS OF THE EXTERNAL EAR

The adult Caucasian ear averages 63.5 mm and 35.5 mm in height and width respectively. The average height and width of a Caucasian female ear is 59.0 mm and 32.5 mm respectively. Generally, people of African descent possess ears that are slightly shorter in length, whereas Asians tend to have slightly longer ears. Proportionately, ear width is typically 50-60% of height. In context with the face, the lateral view demonstrates a “line of balance.” Specifically, the slope of the ear approximates the nasal dorsum to within 15 degrees, or lies approximately 20 degrees posterior to the vertical plane. The superior aspect of the ear rests at the level of the brow.

In terms of ear protrusion, normal distances from the helix to the mastoid are 10-12 mm in the upper third of the ear, 16-18 mm in the middle third, and 20-22 mm in the lower third. On frontal view the helix should project 2-5 mm more laterally than the antihelix. Conchal protrusion from the mastoid is typically 12-15 mm. The angle between the superior helix and mastoid in the aesthetically ideal ear is 20-30 degrees. Prominauris, or excessive protruding of the ears, occurs when angles exceed 30-40 degrees.

REFERENCES

Campbell AC. Otoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery 21:310, 2005. UI: 16575709

Kelley P, Hollier L, Stal S. Otoplasty: evaluation, technique and review. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 14:643, 2003. UI: 14501322

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION / TIMING OF SURGICAL CORRECTION

The incidence of excessively prominent ears is about 5%. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with 25% partial penetrance, and most commonly results from two anatomical irregularities, specifically, the absence of an antihelical fold and excessive depth or projection of the conchal bowl.

Precise analysis of auricular deformities is paramount to achieving successful outcomes. Surgeons must identify the specific cause of auricular prominence in the formulation of an appropriate surgical plan. Although frequently bilateral, asymmetries in ear protrusion should be noted. As such, standard preoperative photography should be performed, including frontal, full right and left oblique, full right and left lateral, and close-up right and left lateral views.

Although there exist proponents of earlier surgical correction, most authors agree that the ideal age for otoplasty is between 5 and 6 years. Physiologically, the auricle is roughly 90% of adult height by 6 years of age. Psychosocially, correction is undertaken prior to or early after entrance to grammar school, where children are subject to peer ridicule. Importantly, by 5 or 6 years, children are able to participate in their own post-operative care (i.e. not pulling off bandages or disturbing the wound).

REFERENCES

Gosain AK, Kumar A, Huang G. Prominent ears in children younger than 4 years of age: what is the appropriate timing for otoplasty? Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 114:1042, 2004. UI: 15457011

TECHNIQUES OF SURGICAL CORRECTION

Over 200 techniques have been described for correction of the prominent ear. Conceptually, they can be subdivided into procedures that address an absent antihelical fold, procedures that reduce excess in the conchal bowl, and those that reduce prominent or enlarged lobules. Most of the above techniques involve reshaping of auricular cartilage, which can be accomplished through a number of cartilage-manipulating techniques such as suturing, scoring, and excision / repositioning, to name a few. Herein, the most commonly employed technique for correction of an absent antihelical fold, originally described by Mustarde, will be discussed in greater detail. In addition, the Furnas technique for reduction of an excessive conchal bowl will be described.

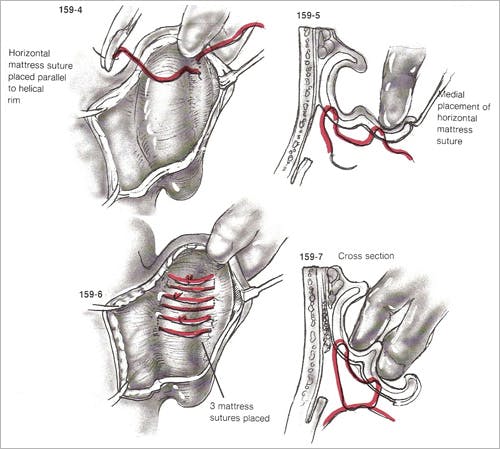

In 1963, Mustarde first described a technique for creating an antihelical fold by utilizing permanent conchoscaphal mattress sutures. Since that time, many subtle refinements of this technique have been described, but the fundamentals of the procedure remain unchanged.

Pediatric patients most commonly undergo general anesthesia for this procedure, and perioperative broad-spectrum antibiotics are administered. The face is prepped into a sterile field such that both ears can be visualized simultaneously. After infiltration with lidocaine 1% with epinephrine 1/100,000, an eccentric fusiform incision is made into the postauricular surface. Typically, more skin is excised from the postauricular surface than from the mastoid, in an effort to camouflage the resultant scar into the postauricular sulcus following setback.

Once the fusiform of skin is excised, the remaining skin of the posterior aspect of the helix, antihelix, and concha is undermined with scissors, leaving perichondrium attached to the auricular cartilage. The extent of antihelical fold creation is determined by pinching the anterior auricle with a thumb and index finger. Alternatively, some surgeons mark cartilaginous landmarks with several ink-dipped fine needles. Permanent horizontal mattress sutures (e.g. 4-0 Mersilene) are placed into the helical cartilage, parallel to the helical rim at the lateral extent of the desired antihelical fold.

(Figure 2)

It is critical that sutures are placed through the cartilage and lateral perichondrium but not the lateral helical skin. The first helical suture is placed at the level of the helical root in order to create the superior crus. The second suture is typically placed just inferior to the junction of the superior and inferior crura. Third and fourth sutures are placed as needed. Some overcorrection is necessary during placement of the most superior suture, as it has been demonstrated that as much as 40% loss of correction at this site may occur within the first postoperative year.

The wound is irrigated with antibiotic solution and closed with resorbable sutures. Antibiotic ointment, along with cotton impregnated in mineral oil, is applied to the new antihelix and postauricular sulcus, and a mastoid dressing is applied.

The dressing is removed on the first postoperative day to check for hematomas, and replaced for 3-4 more days. Subsequently, a head band is worn continuously for 2 weeks and at night for an additional 4-6 weeks.

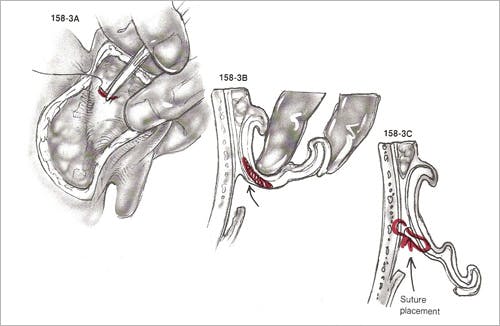

In 1968, Furnas popularized a technique of conchal setback using permanent cochomastoidal suturing. This procedure is often undertaken in conjunction with techniques to correct an absent antihelical fold, as described above.

The patient is prepped and draped in a manner similar to that described for correction of the antihelical fold. After infiltration of lidocaine 1% with epinephrine 1/100,000, a fusiform incision is made in the postauricular region. The width of the incision is estimated by manually pushing the concha towards the mastoid. Care is taken to avoid excessive skin excision, as tension on the wound predisposes to hypertrophic scar formation. Little to no skin excision is required inferior to the level of the antitragus. After excision of skin, soft tissue and postauricular muscle is excised from the postauricular sulcus. Sufficient soft tissue is excised to produce a pocket that will receive the concha during suture placement.

The skin over the helix, antihelix, and concha is undermined with scissors, and permanent horizontal mattress sutures (e.g. 4-0 Mersilene) are placed at the lateral third of the concha cavum and concha cymba parallel to the natural curve of the auriclar cartilage.

(Figure 3)

The sutures are thrown through cartilage and lateral perichondrium, but not lateral auricular skin. At least three sutures are placed for adequate setback. The sutures are placed on what was the ascending wall of the concha, and when tightened convert the wall into a longer floor of the concha. For long-term successful conchal reduction, suture bites of mastoid periosteum must be taken. With extremely thick cartilage, as frequently seen in older individuals, the cartilage may be weakened by excising small vertical ellipses of cartilage. Importantly, conchomastoidal sutures must allow the concha to be set not only medially but posteriorly, as well. If not, external auditory canal stenosis can result.

The wound is irrigated and closed as after the Mustarde technique. A mastoid dressing is placed, and subsequent postoperative management is the same as that of antihelical fold surgery.

Otoplasty Refinement Techniques

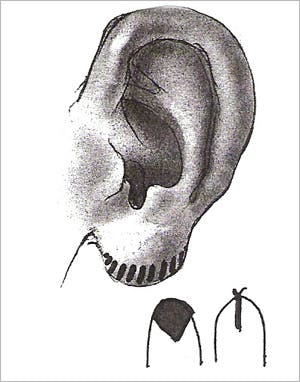

Frequently, small deformities of the auricle are present that can be corrected by subtle surgical refinements. These techniques are applicable to both congenital irregularities and those deformities that are detected following more substantial otoplasty correction (i.e. conchal setback and correction of absent antihelical fold). Such refinements include correction of the prominent lobule and reduction of helical prominences.

Reduction of a large ear lobule rarely requires general anesthesia in the adult population. A new ear lobe size is designed with a marking pen. After infiltration with local anesthesia, a fusiform incision is made anteriorly and posteriorly in a curvilinear fashion, and a V-shaped, wedge excision of lobule excess is performed.

(Figure 4)

The skin is closed with permanent suture (e.g. 6-0 nylon), with suture removal occurring on the sixth postoperative day.

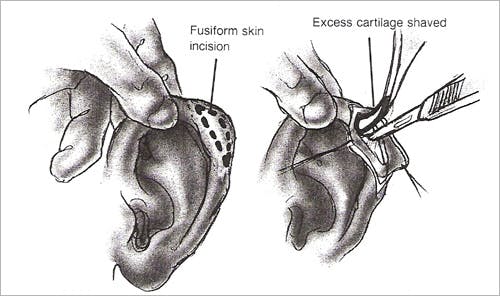

Helical prominences, such as superior outer helical rim cartilage excess (i.e., elf ears, Spock ears) and superior helical fold cartilage excess (i.e., lop ear), may be corrected by a variety of helical reduction techniques. After the infiltration of local anesthesia, a fusiform incision is made on the outer helical rim in the case of helical rim excess and under the helical fold in the case of superior helical fold excess.

(Figure 5)

After skin elevation, excess cartilage is shaved using a blade. Skin is trimmed as necessary to ensure appropriate draping over the cartilaginous rim. The incision is closed with permanent suture (e.g. 6-0 nylon), with suture removal occurring on the sixth postoperative day. No pressure dressing is required.

REFERENCES

Mustarde JC. The treatment of prominent ears by buried mattress sutures: a ten-year survey. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 39:382, 1967. UI: 5336910

Furnas DW. Otoplasty for prominent ears. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 29:273, 2002. UI: 12120683

Adamson PA, Constantinides MS: Otoplasty, in Bailey BJ, Calhoun KH, Coffey AR, Neely JG (eds.): Atlas of Head & Neck Surgery – Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996; p 429.

Overall, there is a high satisfaction rate among patients who undergo otoplasty surgery (85%). Complication rates range from 7-12%, with unsatisfactory aesthetic outcomes accounting for the majority of complications. Complications arising from otoplasty may be subdivided into early, late, and aesthetic/anatomic in etiology (Table 1).

Hematoma formation occurs following approximately 1% of all otoplasty procedures. Studies have suggested a slightly higher incidence of hematoma formation in cartilage cutting procedures in comparison to cartilage suturing operations. Symptoms include unilateral or bilateral ear pain, usually within the first 48 hours following surgery. Hematoma formation may lead to perichondritis and the devastating sequelae of cartilage necrosis and ear disfigurement. Therefore, complaints of ear tightness or pain should be taken seriously with prompt removal of bandages and inspection of wounds. Infections following surgery typically manifest on postoperative day 3 or 4. Treatment involves administration of systemic antibiotics, with particular emphasis on coverage for staphylococcus, streptococcus, and pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Late complications include paresthesias of the ear, particularly to cold temperatures, which typically improve over 4-6 months. Additionally, suture otoplasty techniques may result in complications surrounding permanent suture placement, such as suture extrusion and suture granoloma formation. These risks are minimized by meticulous placement of sutures. Hypertrophic scars or keloids may form as the wound heals, and conservative treatment with serial triamcinalone acetonide injections is indicated.

Aesthetic complications result from abnormalities in the relationship of the auricle to the scalp or from distortion of the auricle itself. These often stem from overcorrection or undercorrection of the initial deformity. Often, an unsatisfactory outcome occurs when there is asymmetry between the left and right ear (typically, less than 3 mm difference in the mastoid-helical distance between left and right ear is satisfactory). Classic deformities include the “telephone ear” deformity that results from overcorrection of the middle third of a prominent ear. “Reverse telephone ear” deformity occurs when the midauricle protrudes after overcorrection of the superior pole and lobule. Alternatively, inadequate conchal setback may produce a similar aesthetic deformity. Isolated antihelical overcorrection, or “hidden helix,” produces the suboptimal appearance of the helix positioned medial to the antihelix on frontal view. All of the above aesthetic complications can usually be addressed through revision surgery, if desired by the patient.

REFERENCES

Becker DG, Lai SS, Wise JB, Steiger JD. Analysis in otoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 14: 63-71, 2006.

SUMMARY

Protrusion of the ears is a relatively common deformity. Successful surgical correction can relieve both children and adults alike of the psychosocial distress often associated with these deformities. An understanding of auricular anatomy and aesthetic ideals, coupled with accurate analysis and meticulous surgical technique, can yield outcomes that are gratifying to both patient and surgeon. (Figure 6)

FIGURE LEGENDS

Figure 1 – External landmarks of auricle with intact skin (A) and corresponding cartilaginous landmarks (B) (from Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL: Surgical Anatomy of the Face, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, p 171-172.)

Figure 2 – Technique of Mustarde for creation of the antihelical fold – three permanent horizontal mattress sutures are placed parallel to helical rim. Care is taken to place sutures through anterior perichondrium without violating the anterior skin. (from Adamson PA, Constantinides MS: Otoplasty, in Bailey BJ, Calhoun KH, Coffey AR, Neely JG (eds.): Atlas of Head & Neck Surgery – Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996; p 429.)

Figure 3 – Technique of Furnas for correction of conchal excess – permanent conchomastoid horizontal mattress sutures are placed at the lateral third of the concha. A full-thickness bite of cartilage and perichondrium is performed, with care taken to avoid suture placement through the anterior skin. Additionally, the sutures must pull the ear posteriorly, as well as medially, to prevent stenosis of the external auditory canal. (from Adamson PA, Constantinides MS: Otoplasty, in Bailey BJ, Calhoun KH, Coffey AR, Neely JG (eds.): Atlas of Head & Neck Surgery – Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996; p 429.)

Figure 4 – Fusiform wedge excision for reduction of large ear lobule. (from Adamson PA, Constantinides MS: Otoplasty, in Bailey BJ, Calhoun KH, Coffey AR, Neely JG (eds.): Atlas of Head & Neck Surgery – Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996; p 435.)

Figure 5 – Reduction of helical prominences. (from Adamson PA, Constantinides MS: Otoplasty, in Bailey BJ, Calhoun KH, Coffey AR, Neely JG (eds.): Atlas of Head & Neck Surgery – Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996; p 435.)

Table 1 – Complications of Otoplasty (from Becker DG, Lai SS, Wise JB, Steiger JD. Analysis in otoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 14: 63-71, 2006.)

Figure 6 – (a, b, c) Young man with prominauris, specifically conchal excess and an absent antihelical rim. (d,e,f) patient 4 months postoperative from antihelical fold creation and conchal setback using suture techniques.