Alar Retraction: Etiology, Treatment, and Prevention

Abstract

Objective: to determine etiology and treatment of alar retraction based on a series of specific rhinoplasty maneuvers

Design: retrospective review of a single surgeon’s (MC) rhinoplasty digital photo database, examining pre-operative alar retraction from 2003 to 2005 in 520 patients. Patients with more than 1 millimeter (mm) of alar retraction on pre-operative photographs were identified. Post-operative photographs were examined to determine the effect of specific rhinoplasty maneuvers on the position of the alar margin; these maneuvers included cephalic trim, cephalic positioning of the lower lateral cartilage, composite grafts, alar rim grafts, alar batten grafts and overlay of the lower lateral cartilage.

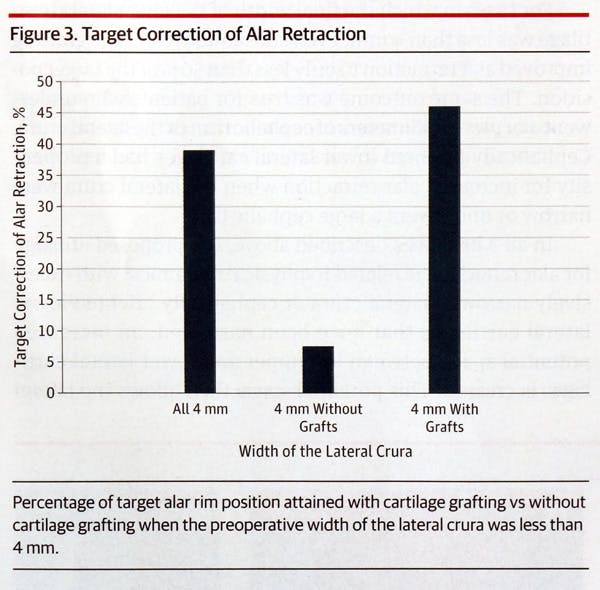

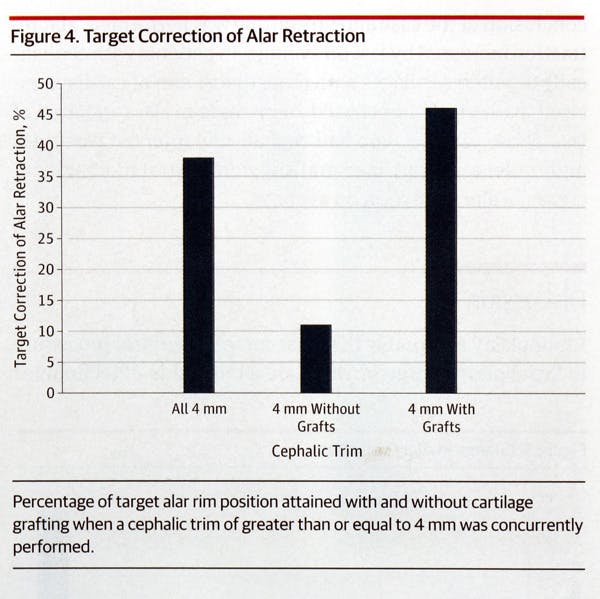

Results: 45 patients with alar retraction met inclusion criteria, resulting in 63 nasal halves with alar retraction. Forty-seven percent of the patients (n=21) had prior surgery; 47% of the patients also had cephalically positioned lower lateral cartilages. Among patients with less than 4 mm of cartilage width at the outset, 46% of those who received supportive grafts achieved target correction, versus only 7% for patients who did not undergo supportive cartilage grafting. In patients who underwent more than 4 mm of cephalic trim , those who received supportive grafts achieved 46% of target correction, versus 11% among those who did not.

Conclusion: Alar retraction is a highly complex problem which can be improved with structural supportive grafts.

Keywords: composite graft, alar rim, alar margin, alar retraction, rhinoplasty

Alar retraction is classically thought to be an unsightly stigmata of overly aggressive rhinoplasty. However, it has been the authors’ experience that alar retraction is also prevalent in the general population, and can be seen in patients without a prior history of rhinoplasty. In addition to the unfavorable aesthetic appearance, alar retraction may also have functional consequences manifesting in collapse of the external nasal valve.

In the analysis of alar-columellar disproportion, alar retraction can be identified by the presence of alar notching, weak lateral crura, retraction of the alar margin, or excessive curve to the alar rim margin. These various etiologies can be congenital or acquired.

The theory behind iatrogenic alar retraction is that aggressive resection of the cephalic portion of the lower lateral cartilage will lead to weakening of the cartilage causing it to retract superiorly. A central tenant of rhinoplasty surgery espouses the preservation of a critical width of the lateral crura—typically 8 to 10 millimeters (mm)—to maintain the structural integrity of the cartilage framework.

Division, and in some cases removal, of the soft tissue and ligamentous attachments of the lower lateral cartilage may weaken its support structure, and render it more susceptible to upward retraction. Medially, the alar cartilage has ligamentous connections to the nasal septum. Laterally, the accessory cartilage serves as an attachment for the lateral crus to the pyriform aperture to form the lateral crural complex . Cephalically, the alar cartilage has fibrous attachments to the upper lateral cartilages. During rhinoplasty, these attachments are subject to disruption. Moreover, resection of the actual cartilage not only decreases the structural framework of the nostril, it also removes the adjoining supportive attachments, thereby further weakening the alar cartilages.

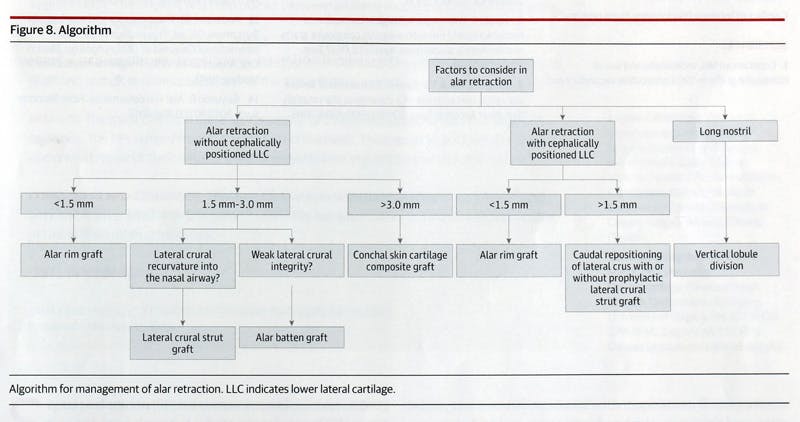

Treating patients with pre-operative alar rim retraction can be managed with several different techniques. Typically, repair of alar rim retraction requires cartilage grafting in order to effectively lower the nostril margin. Determining which technique is best suited to a particular alar retraction can be a challenge.

Surgeons seeking to avoid and correct alar retraction are forced to rely on the experience of other surgeons, rather than compelling objective data. We sought to analyze the meticulous records of the senior author (MC) to determine which maneuvers were most effective in improving alar retraction, and which cartilage states were most likely to result in retraction of the alar margin.

Methods:

An Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective analysis of the senior author’s (MC) rhinoplasty database was performed to identify all patients who underwent primary or revision rhinoplasty from January 2002 to December 2005. In total, 520 patients were found. From this group, all patients with pre-operative alar retraction greater than 1 mm on lateral view were identified. All patients had a minimum of 6 months post-operative follow-up.

Pre- and post-operative photographs were taken with a Canon EOS 5D digital single lens reflex camera with a 105 mm macro lens (Tokyo, Japan) in a standardized manner. Distances were measured only on lateral view as previously described. Preoperative measurements were obtained using Adobe Photoshop® (San Jose, California).

Alar retraction was identified by Gunter’s classification system. A line was drawn from the anterior to the posterior apex of the nostril. A perpendicular to this line was then drawn to the point of maximal retraction. An additional line was drawn that would create the ideal level of alar retraction, which should be 1-2 mm above the anterior to posterior apex line. For consistency, the ideal line was determined to be 1 mm above the anterior to posterior apex line, and was defined as the “target” level of alar retraction. Post-operative photographs were then analyzed to determine the post-operative alar retraction distance. The post-operative measurements were compared to pre-operative values. A fixed data point from the midpoint of the tragus to the lateral canthus was used to derive a multiplier to standardize lengths between photographs. This allowed an objective means of comparing pre- and post-operative photographs .

The senior author utilized detailed rhinoplasty worksheets to document the amount of cartilage removed, the amount that was preserved, and the size and location of any cartilage grafts that were employed. Calipers were used for all intra-operative measurements . For patients where cartilage splitting techniques were utilized, the amount of overlap was measured. In addition, patients with cephalically oriented cartilages were identified on pre-operative photography, based on the presence of lower lateral cartilages that were aligned with the medial canthus rather than the lateral canthus. The relative length of the nostril to the alar retraction was also calculated.

Statistical analyses took place with a one-tailed student t-test comparing pre- and post-operative values.

Results

In total, 45 patients were identified with alar retraction, resulting in a total of 63 retracted alar rims. Twenty-one of the 45 patients (47%) had undergone previous rhinoplasty, while the remaining 24 subjects were primary rhinoplasty patients. Twenty-one of the 45 patients (47%) with alar retraction were found to have cephalically oriented cartilages.

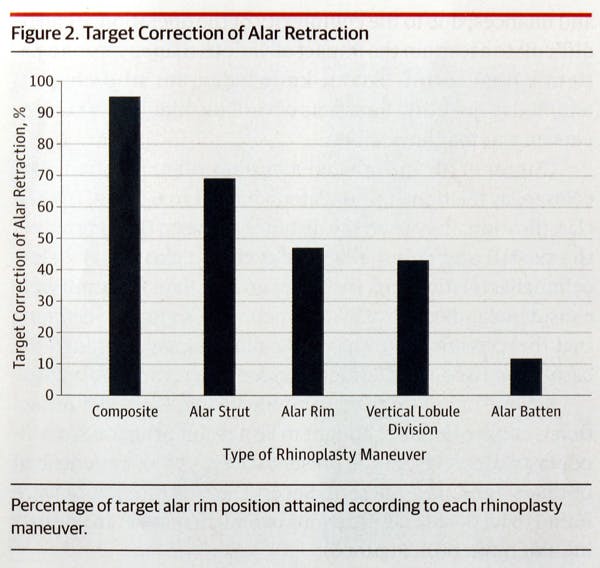

Figure 1 demonstrates the percentage of target correction of alar retraction which was achieved with various techniques in isolation (i.e. without the use of another graft). Composite grafts achieved 95% of their target correction value, while alar strut grafts achieved 69%, alar rim grafts achieved 47%, vertical lobule division achieved 43%, and alar batten grafts achieved 12% of target correction values.

Figure 2 examined the effects of grafting when less than a 4 mm width of lower lateral cartilage was present at the outset of the case . In instances where grafting occurred, the alar retraction was improved to 46% of the target goal on average, while without grafting the alar retraction only improved 7%.

In patients with 4 mm or more of cephalic trim excised, those who received cartilage grafts reached 46% of their target goal, while patients without cartilage grafts achieved only 11% of their target goal.

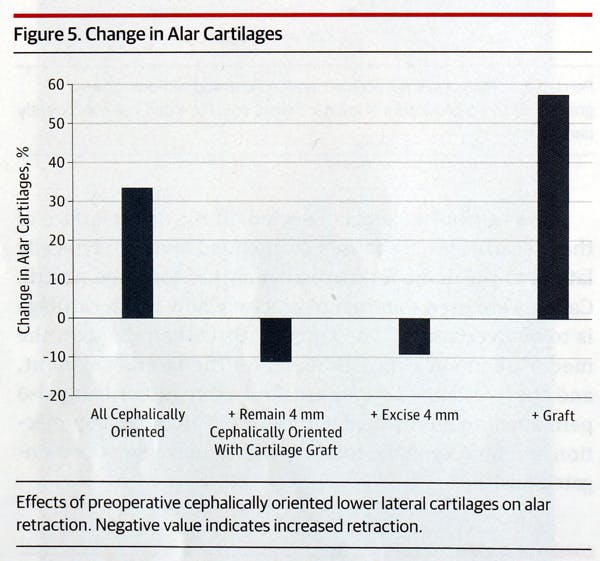

The effects of cephalically oriented cartilages were also examined. In all patients with cephalically oriented lower lateral cartilages, 32% of target correction was achieved. In patients with cephalically oriented cartilages where less than 4 mm of cartilage remained at the conclusion of the case and no grafting was performed, patients demonstrated increased alar retraction of 11%. In patients with cephalically oriented cartilages with more than 4 mm of cartilage excised, patients demonstrated an increase in alar retraction of 9%. Patients with cartilage grafting and cephalically oriented cartilages demonstrated improvement of 54% in alar retraction.

Another measure was taken comparing the nostril length to the amount of alar retraction. When the patient’s nostril was long pre-operatively, which we defined as a nostril length to alar retraction ratio of 4:1 or greater, these patients benefited from vertical lobule division; with this maneuver, these patients achieved 43% of target position of alar retraction.

Comment

Rhinoplasty is arguably the most complex surgical procedure in facial plastic surgery. There are a multitude of techniques and nuances; due to the complexity of the operation it can be difficult to ascertain the impact of various maneuvers on the patient’s final result. To the authors’ knowledge, there is no study that has attempted to quantify the effects of various rhinoplasty maneuvers on alar margin position.

Gunter et al. introduced a system which classified alar-columellar relationships on lateral view into six types. In his classification, he used the distance between the long axis of the nostril and columella or alar rim to classify the alar-columellar relationship. Distances greater than 1-2mm were considered indicative of alar retraction.. Guyuron, claiming that this classification was only two-dimensional, included the basal view to add three additional classes of alar rim deformities. According to Sheen, the alar-columellar relationship should be examined on lateral view, and the ideal amount of columellar show is 2-3 mm.

Several of our findings were surprising. Firstly, alar retraction is conventionally thought to be a result of aggressive rhinoplasty. However, in the present study, 53% of subjects were primary rhinoplasty patients. Composite grafts were found to be the most efficacious in improving alar retraction.

Cases with a final width of the lower lateral cartilage which was less than 4 mm, even with subsequent cartilage grafting, improved their alar retraction level to less than fifty percent of the target level. The same outcome was true for patients who underwent 4 or more millimeters of cephalic trim of the lateral crura. It is theorized that this may be due to an increased potential space between the upper and lower lateral cartilages, which has allowed the alar margin to retract superiorly. In all cases, the target level of the alar margin was more readily achieved when cartilage grafting was employed.

Cephalically oriented lower lateral cartilages had a propensity for increased alar retraction when the lateral crura were narrow, or underwent a large cephalic trim. In these individuals, it may be prudent to prophylactically employ cartilage grafting to prevent the future development of alar retraction.

To our knowledge, this is the first paper to define the “long nostril” patient. The long nostril patient is often seen with a slightly dependent tip on lateral view, creating a slight “snarled” appearance. Correction of this was obtained with lower lateral cartilage overlay, which achieved nearly 46% of target correction.

This study is limited by a short follow-up duration of only six months. While follow-up of more than one year would be desirable, in a diverse international practice (MC) it is often difficult to obtain reliable patient photographs and follow-up after one year.

Conclusion:

The results of this study objectively confirm that which is intuitively suspected: that over-resection of the lateral crura can lead to alar retraction, and cartilage grafting has a measureable effect on improving this retraction. As each patient is different, the ideal method of cartilage grafting is difficult to dictate, and will depend on etiologic factors and on surgeon experience. Future research to determine the optimal techniques for various etiologies of alar retraction would be beneficial.